Light/The Holocaust & Humanity Project

- Choreographer: Stephen Mills

- Music: Steve Reich, Evelyn Glennie, Michael Gordon, Arvo Part, Philip Glass

- Costumes: Christopher McCollum

- Lighting: Tony Tucci

- Set Design: Christopher McCollum

- World Premiere: Ballet Austin, April 1 2005

- PBT Performance Date: November 12-15, 2009

Program Notes

Program Notes (November 2009)

By Carol Meeder, former Director of Arts Education

Although no artistic representation of the Holocaust can accurately express the catastrophic events endured by innocent victims of this period of history, Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project humbly seeks to speak about the human issues embedded within it. These issues are of family, culture, segregation, deportation and indiscriminate decisions made daily about life and death. This work follows the experiences of one survivor, from the loss of her family to her liberation and the illumination of human relationships encountered along the way. – Ballet Austin

Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project has inspired the most extensive list of partners that Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre has ever gathered for any production. The collaborative effort of this project includes arts and culture organizations across the City of Pittsburgh who contributed their talents to raise awareness and educate future generations about the events of the Holocaust, the valuable talent that was lost, and the hope that remains and enriches our lives.

The sharing of survivor Naomi Warren’s personal journey, as told in dance, is a unique opportunity for an audience to hear the story, feel the emotions and reflect on the impact of an experience that defies description. The arts provide different ways of viewing the happenings of history and this work of dance stands apart with its sensitivity.

The ballet is divided choreographically into seven sections: Adam and Eve, Family, Targets Behind Doors, Isolation and Degradation, Boxcar, Ashes, and Hush. The music is from five composers Steve Reich, Evelyn Glennie, Michael Gordon, Arvo Part, and Philip Glass. As the ballet unfolds, one can see and hear how the choreography and music change with the focus and emotions of the journey.

Regardless of the devastation, the message of this work is one of hope and promise for the future even as so many had to struggle to stay strong in the face of horrific adversity. The lessons of history should never be lost on the future.

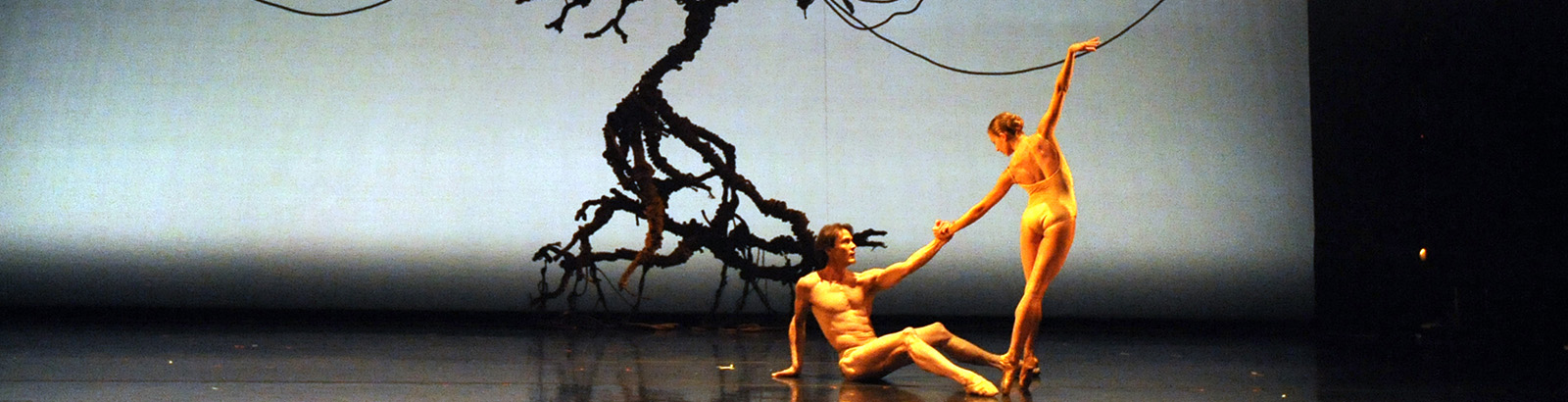

In the “Adam and Eve” and “Family” sections of the ballet, joy exudes in the creation of mankind and its proliferation into family groups celebrating love and joyous occasions. The women’s voices and ethnic melodies of Steve Reich’s Tehillim celebrate the development of a people with love, intelligence, values, beliefs and traditions.

As the ballet moves into sections three and four, “Targets Behind Doors” and “Isolation and Degradation”, the atmosphere changes from joy to confusion and fear. The choreography, acting and music follow the mood and everything changes. Often audiences forget that a dancer is also an actor. Facial expressions, as well as choreography, tell the story. After the celebration of the first act, watch how the transition heralds the beginning of an event that never ceases to impact our world. The sudden, unexpected occurrence of Kristallnacht, or Night of Broken Glass, and the ensuing events are accompanied by the somewhat hollow and relentless sounds of the marimba in Evelyn Glennie’s Rhythm Song.

After the shock that one’s own countrymen could exercise such hatred, destruction and devastation on entire families and social groups, the frightening transport began. They were taken from their homes, isolated in filthy ghettoes and then herded into small wooden boxcars to be taken to prison and death. In this “Boxcar” section, Stephen Mills’ choreography reflects the tight, intimate, stifling conditions in which many died before reaching their ominous destinations. The music, Michael Gordon’s Weather is at the same time appropriate, reminiscent, irritating and intensely frightening.

“Ashes”, the title of the next section, leaves nothing to the imagination. The outcome – extermination and cremation – is ultimately a singular event. Regardless of the number in the masses, each individual death is a personal experience. Tabula Rasa, composed by Arvo Part, accompanies and mourns the loss, one person at a time, with a string orchestra that begins intimately with a lament on a single instrument, then builds to a frenzy before retreating to its somber conclusion. The dance reflects helplessness and inevitability, as well as balancing individual identity and loss with the strange camaraderie of an inconceivable brotherhood.

The stories of survivors are themselves lessons of hope, perseverance and faith. Their message is a legacy for the future, to never forget and never allow the next generations to forget.

The concluding section of Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project closes a saga of wrenching and turmoil with peacefulness. The music of Philip Glass’s Tirol Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, as played by Dennis Russell Davies, quiets the soul. It allows the mind and body to release the tension, embrace freedom, begin the healing and look ahead. The choreography of this “Hush” section is freer, gentler, and subdued. As the dancers move smoothly and calmly across the stage, the mood is not one of relief or joy, but rather of reflection and hope.

It has been a privilege and an honor for Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre to present Stephen Mills’ Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project and to share this wonderful expression of an artistic vision. The following personal message from Mr. Mills is a charge befitting all of us:

Art alone does not change the world, people do. We all have to be diligent to individual and governmental protection of human rights whether or not we agree with other’s religious and political choices. Acts of moral blindness did not go out in the 1940’s with the liberation of Auschwitz.

Before coming to see Light / The Holocaust & Humanity Project, try to reflect on an instance when you were a bystander, a victim, or a perpetrator of intolerance. Use this work to reflect upon your own responsibilities when confronted with acts of bigotry and hate. My hope is that this work sparks your interest, which in turn starts a conversation. People engaging in dialogue begin the process of positive change.